I was born and raised up in Germany, but since September 2016 I am living in Kosovo, volunteering in GAIA, an environmental human rights and peace organization and SCI branch of Kosovo. I am working with kids in “Imaginatorium”, an alternative educational centre and supporting the work in GAIA- currently planning and preparing workcamps, doing promotion of volunteering and also doing volunteer placement. Besides being active in GAIA, I like be outside in the calm and in the nature, and to learn, to observe and transform the world around me through all kind of media and arts, using them as a tool to tell stories.

Moria- the surroundings of the camp

Our paths through the Island of Lesbos also led us through the village of Moria, situated at around 1,5 km distance from the barbwires of the camp of Moria on the flanks of a hill covered in olive trees.

The village seems to sleep as we walk through its streets- on its highest point a stony church in that’s shade two boys suck their time from cigarettes and replace it in the world as grey vapor. The view from the church’s portal directs into the hills covered in olive groves, that’s silvery green is pierced by the cubic white of Moria camp’s housing containers, fences, and pylons. Moria camp is a “hotspot” that gathers all new arrivals on the island in order to register and separate them and facilitate asylum application process for those who are considered to be in a situation endangering enough to ask for asylum. All new arrivals are being restricted to move and have to stay in a fenced area of the camp for 25 days, before they are allowed to resettle in other areas of the camp or move to different campsites.

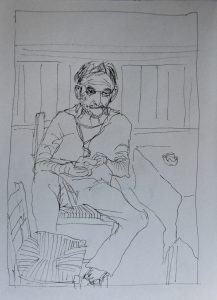

As we dive back down into Moria’s sleeping streets, we pass an abandoned playground, overgrown by dry grass, a caterpillar from steel rigidly steering through the coloured fence. The energy that Morias inhabitants seem to invest into the tidiness of their houses and yards desperately aims to push back the slow death of the village. Empty buildings are being torn down by time and space, the facade of a building still advertises the past, through its windows the sky and backyard pierce onto the streets. The center of the village -an accumulation of small shops and three Kafenions, greek coffee bars, that are all occupied by men, who pass their time searching for the bottoms of their bottles of ouzo and wine.

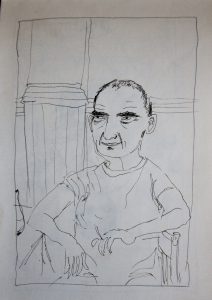

Following the invitation of one of those sitting, we enter a Kafenion that seems to be a shrine, conserving the past in photos of the owner playing in the local football team, and his family in the Café dating back to the 1970’s. We are being served coffee by the only woman in the place, with hair precisely cut into a bob, her eyes underlined with water blue of the Aegean Sea. (pic 4)

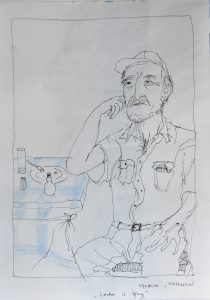

Marios, whose invitation we followed, is the only one of the four men inhabiting tables on each corner of the luminous Kafenion, who knows a bit of English- remains of a former life in the US, where he used to be working in fashion industry. He left daughter and son there.

We try to investigate how the camp that is only a fifteen minutes’ walk far from the centre effects the life in the village. Marios tells us about around 5000 people living there, each of them supported by the EU with 400 € per month. A note of disappointment flows out of his mouth as he chews out that information. Tells us, how the money that is supposed to support the Greek population gets lost in serpentines and meanders of lies, and that for normal people like him on the end of the chain there is nothing left. Consequently, he has to spend his Saturdays in a Kafenion, in compliance with three other men trying to conserve memories of their past in alcohol, in order not to drown in the non-secure present.

We enter a shop, close to the Kafenion, where a man and a woman in their 60s and 80s sit and chat in the shelter from the sun. He speaks of 1000 people living in Moria, and as Marios before he mentions a high police presence around the camp and in the village. Those who have permit to exit the camp come often to his shop in order to buy food, since the food served in the camp is not eatable. As we ask him for the way to the camp, he tells us: “Just ask one of the guys from the camp. It’s those with the dark skin.”

Eventhough on this very Saturday afternoon we cannot find a lot of the people from the camp in the centre of Moria, we find our way. An abandoned oil mill points out the border between village and the fields. As we approach the camp of Moria, we pass by a wild camp in the olive groves.

On the flanks of the concrete-fence-barbwire constructions that constrict the Containers of Moria Camp, an accumulation of large white tents builds the Red Cross Camp. Right next to it, we enter a warehouse. We meet the two women who, in a collaboration, opened a shop in one corner of the warehouse, in order to provide the people living in the camps with more affordable and easily reachable food.

Enthroned behind the counter of the improvised shopping corner in the vast darkness of a warehouse that was originally meant to supply hotels, the “Mother of Moria”, a woman in the end of her fifties, operates the cash, giving all of her customers a benevolent smile and some nice words on the way, before they pass the door. “I know them all.” She says. “They are like my children, they come to me to ask for help, if they need something. I try to help them as I can, and they invite me in return to come to their tents, have a coffee or tea with them. This young man here came to me once in the morning and told me that he could not sleep for the whole night because they were put with 32 people in one of those containers with 6 beds, and there was too much noise.” She continues: “I feel sorry whenever I witness those moments- and the camp bears a lot of them. They put the containers because of the incident that happened in November 2016. Moria was a camp all built of tents, and in one of them, a gas can have had exploded, and a child and its grandmother died in the flames, another 2 people were transferred to hospital on the mainland with serious injuries. After there were riots in the camp -at that time hosting more than 3000 people- to address the miserable living conditions, and through the pressure coming from Human Rights Organizations, requesting to improve the standards in the camp, they installed containers. So now they stock the people in them like chicken in breeding factories.”

We are about to move when a young man, white T-shirt, the Blue jeans knee-long, his half-long hair accurately held by a black ribbon, pops into the warehouse. He comes to get a big knife for cutting Schwarma, that they are preparing for the first evening of Ramadan. We start to talk- us initially not being sure about the identity of the young men we are facing- his attitude could be the one of a local Greek volunteer. But he is from Bagdad, arrived 9 months before on Lesbos, passed through Moria and volunteers now in the NGO Humans4Humanity, an US-american initiative that runs a centre close to Moria camp and provides food, clothing, schooling activities and community support for people who turn towards them, searching for help- not making difference between local people in need and (relatively) new arrivals.

Ahmed*takes us to the organizations’ close by community centre, the House of Humanity. It is situated on the opposite of a military camp on the flanks of the hill. An abandoned warehouse, transformed through new colourful wall paintings and some space holders into an improvised day-centre, home for the people who don’t have a better option to stay. On the entrance, the reception that hands out the food tickets for the food station that offers basic elements such as sugar, rice, baby food… Children enjoying themselves with plastic toys, Schwarma for the evening roasting on the spit in the cooking tent, some young families sitting around, talking, playing with their children.

Neda Kadri, the coordinator of Humans4Humanity explains us their situation: “We are trying to support the people who are in need, who are away from their homes and a life-sustaining security. Our principles are to treat people by honouring them as dignified humans, therefore giving them the opportunity to choose what they need. We have this clothes shop, where they can choose what they want to wear, and our food corner where they are able to choose what they want to eat. Humanitarian aid is always in the risk to be harming people’s dignity, because you are pushing them into this state of being dependent. You are basically deciding for them, don’t giving them much space to be active, to be subjects. That’s what we want to change. We are employing people just as Ahmed, who came not long time ago, supporting them by providing accommodation together with volunteers that join the project from abroad, and therefore giving them the chance to start a new life here and do something meaningful, helping other people that are in the same situation that they went through.”

The area of Moria is a weird split between realities, fences being held up to desperately separate them, enabling people to close their eyes and others to proceed in the unseen. Yet those who stay awake are trying to take down those fences, in order to keep up a togetherness in mutual support and activity for a more human environment. But it’s an unequal balance act, one of those indicators of a world lost in a general disorientation of values and their realization.

For more information about Humans4Humanity, follow this link: https://www.facebook.com/Humans4HumanityOrg/